When an incident occurs, pipeline transport invariably attracts negative media attention. When a failure makes the news, one of the questions I am almost always asked by people not in the pipeline business is: “Why does this keep happening? It never used to.”

The unfortunate truth is that even though pipelines are one of the safest and most reliable forms of energy transportation, there is a long history of pipeline failures that have helped shape industry regulations in the United States.

The requirements and regulations in place today actually make them exponentially safer than they were decades ago. For example, prior to the 1930s, natural gas was not even required to be odorized with Mercaptan (the rotten egg smell), which we all associate with a gas leak today. So how do pipe failures impact the regulations in place today and those that are still forthcoming?

How Regulations Take Shape

When you look at regulations, they are vague. They are purposefully designed that way—to be open to interpretation in order to accommodate the multitude of operators that transport natural gas in this country. As a result, if you present a regulatory rule to a room of 30 different operators, you would get 30 different responses. This is because their systems work differently based on their operating environments, the age of the infrastructure, the number of mergers and reorganizations that the company has undergone, etc.

As with anything vague, there are gaps for misinterpretation, which are identified and brought to light when failures occur. When these shortcomings are identified through root-cause analyses, they typically lead to either the creation of new regulations or further clarification of the existing rules.

This is one of the reasons that regulations are constantly under review and sections are added, removed and constantly clarified through FAQs and guidance material. To start, those not in the pipeline industry need to understand the chronology of how we got here as a nation.

Historical Snapshot of Pipeline Regulation in the U.S.

Prior to the early 1970s, pipelines were not under any type of regulation and were typically installed to industry standards. One of the first and most deadly pipeline failures actually occurred in 1937, well before any sort of regulations governed pipeline installation. A total of 294 students and teachers were killed in a school house near Dallas, Texas by a natural gas explosion.

In response to this incident, the United States Natural Gas Act (NGA) was created in 1938 to recommend safer installation practices. This Act established the Federal Power Commission, which ruled for the odorization of natural gas so that a leak could be detected more easily.

Another failure in the 1950s demolished an entire row of houses in Rochester, New York. A total of 38 were injured and two children died from the series of blasts that destroyed or damaged an estimated 54 homes. Two years later, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) and the American National Standard Institute (ANSI) created the first version of ASME B31.8, American Standard Code for Pressure Piping Gas Transmission and Distribution Systems, but it was not yet a law.

Years later, in 1965, another gas explosion killed 17 outside of Shreveport, Louisiana, and the Pipeline Safety Act of 1968 was put into law. This Act later established the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 49 Part 192 to regulate the transportation of flammable, toxic or corrosive gas. Part 192 still governs today’s natural gas infrastructure design and maintenance activities, with few substantial changes over the years.

Over the following decade, a series of serious pipeline failures of both natural gas and liquid pipelines occurred during these years, in these places:

- 1993 in Reston, Virginia

- 1994 in Edison, New Jersey

- 1999 in Bellingham, Washington

- 2000 in Carlsbad, New Mexico

Shortly thereafter, the Pipeline Safety Improvement Act of 2002 facilitated the creation of three Integrity Management rules that were implemented into law: 192 Subpart-O for gas transmission, 192 Subpart-P for gas distribution, and 195.452 for hazardous liquids. (Related reading: The 3 Stages of Corrosion Failure Analysis.)

Unfortunately, as we continue our walk through history, less than a decade later we saw another grouping of serious pipeline incidents, which included:

- Michigan Kalamazoo River oil spill in July 2010

- San Bruno, California gas explosion in September 2010

- Wayne, Michigan gas explosion

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania gas explosion in 2011

- Fairport Harbor, Ohio natural gas explosion in 2011

- Allentown, Pennsylvania gas explosion in 2011

- Minneapolis, Minnesota gas explosion in 2011

- Harlem, New York gas explosion in 2014

These incidents have resulted in the revision of several parts of CFR Part 192 (natural gas) and 195 (hazardous liquid), which are both greatly impacted by the newest upcoming and partially implemented regulation: the Pipeline Safety and Job Creation Act of 2011.

So, what has caused this latest spike in larger events, even though more and more regulations keep coming out? Many would blame America’s aging infrastructure. (Watch VIDEO: John Oliver on America's Crumbling Infrastructure.) Most engineering designs have a 50-year design life and that is a major contributor to these failures.

However, in addition to age, another reason is believed to be paramount in these most recent failures: the lack of information that companies have at their disposal to determine the real risks associated with threats to their pipeline systems.

The Regulatory Impact of the San Bruno Pipeline Failure of 2010

One of the most significant findings of the 2010 San Bruno incident was that required pipeline information was not readily accessible to engineers and personnel performing threat and risk analyses on the pipeline for integrity management purposes. As a result, they were assessing it for the wrong problems. The San Bruno incident occurred on a pipeline that fell under the stricter pipeline 2002 higher pressure transmission integrity rule.

So why did the San Bruno incident happen? Shouldn't the 2002 integrity rule have caught it?

Figure 1. The San Bruno explosion resulted in the death of eight people and the destruction of 37 homes.

In non-compliance terms, they applied testing methods correctly, but didn’t have enough information to determine if they were looking for the right problems. It was the lack of information and tight time schedules that contributed to the real threats on the system being misidentified.

The San Bruno pipeline was assessed using a method called Direct Assessment (DA), which is made up of complementary External Corrosion Direct Assessment (ECDA) and Internal Corrosion Direct Assessment (ICDA) methods. Both methods are approved by the code to address non-stable threats of external and internal corrosion and, with special considerations, third-party damage to natural gas systems. The misstep was that this pipeline had other threats that caused stress risers along the pipeline, resulting in the catastrophic failure.

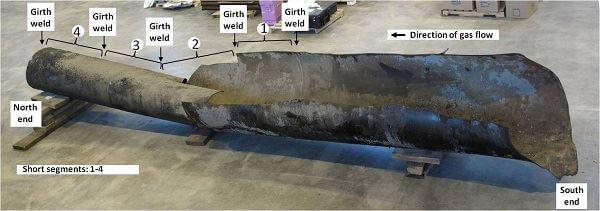

It was determined, after a complete analysis of the pipeline segment (pictured below), that additional threats caused the pipeline to fail:

- Construction techniques/practices

- Manufacturing techniques (low-frequency electric resistance welded (ERW) pipe is prone to seam failures as seen in the linear tear along the pipe)

- Equipment failure (resulting in an over-pressurization of the line)

Figure 2. Analysis of the San Bruno failed pipeline segment.

Figure 2. Analysis of the San Bruno failed pipeline segment.

The DA testing process cannot pick up threats associated with seam and construction weld-related concerns. This failure not only increased the attention that pipelines receive all over the country now, but also the need for infrastructure funding and the increased consequences of catastrophic failures like the one that occurred in San Bruno.

At $1.6 billion, San Bruno resulted in the largest fine to a public utility company to date. Prior to that, the largest fine levied was $101 million against El Paso Natural Gas for an explosion in 2000 near a campground in Carlsbad, New Mexico.

The Pipeline Safety Act of 2011

Passage of the 2011 Pipeline Safety and Job Creation Act was a direct result of the aforementioned pipeline failures over the preceding decade. The Act brings to light many of the industry’s current buzz phrases like “MAOP Validation”, “Valve Automation” and “Seam Threat” to assist in ensuring the reliability and modernization of the nation’s pipeline infrastructure and the safety of the public.

It also set a precedent for how the industry is to monitor their integrity plans, and sparked the July 2014 release of “Guidance for Strengthening Pipeline Safety Through Rigorous Program Evaluation and Meaningful Metrics”, which recommends further steps that operators should take to ensure the safe operation of their pipelines.

In addition, the Act suggests re-examining pipeline threats and assessment selections to determine if the most appropriate assessments are still being utilized for the threats facing their specific systems and pipelines. Furthermore, it set the wheels in motion for the $54 million grant recently awarded by the federal government, which will assist state regulatory bodies with funds for the additional oversight of their local public utility companies. Not only are these grants imperative for our Federal/State partnership to work, they demonstrate our commitment to the American public that we are serious about helping to make our utility lines the safest and most reliable in the world.

According to U.S. Transportation Secretary, Anthony Foxx, “These grants ensure State programs have the funding they need for resources, including personnel and equipment, to protect communities, carry out inspections and enforce pipeline safety regulations that keep the entire pipeline network as safe as possible.”

The Pipeline and Hazardous Material Safety Administration (PHMSA) also recently awarded close to $2 million to universities in order to research new ideas and technologies that will improve the safety of the nation's energy transportation pipelines.

In Summary

This additional oversight and research funding will provide assistance, but it really comes down to prudent operation and qualified personnel performing the integrity assessment work.

Qualifications are two-fold: industry experience and historical knowledge is greatly beneficial, but you have to marry that with an appetite for change and continual improvement. Engineers and professionals in the pipeline integrity field need to remain abreast of regulations and failures, staying up to date on why failures are occurring so that knowledge can be applied to systems before they result in additional failures and consequential government mandates. (Additional reading: Corrosion Prevention for Buried Pipelines.)

One thing remains certain: we are moving in the right direction, but is it fast enough? Time will tell and motivated professionals will help us get there.