November to March is a beautiful time of the year in the wintry climate of the United States and Canada. People participate in all kinds of wintertime activities. It is also the time that owners of marine vessels working on the Great Lakes use to do repairs and maintenance, including painting for corrosion prevention. Although the weather during this time poses many challenges, necessity has been the mother of invention in coming up with equipment and products to meet this challenge.

There are a wide variety of vessels that ply the Great Lakes. These include 1000-foot bulk carriers, passenger ferries, barges and research vessels. Although the size and focus of each vessel is unique, the one common denominator is taking time during winter lay up to do maintenance, including applying protective coatings. This can be very challenging as ambient temperatures are almost always below 32°F (0°C), very often below 20°F (-7°C), and occasionally below 0°F (-17°C). Despite these harsh conditions, painting does take place on the exterior hulls, unheated cargo holds, superstructure, ballast tanks and decks of many vessels.

Timing and Cost of Preventive Coatings

When a vessel comes into a dry dock, many work items are usually scheduled. These can include hull surveys, bearing and shaft repairs, propeller maintenance and painting. The commercial bulk carriers, in particular, are usually in need of a paint job from the keel to the top rail, bow to stern. Damage to the vessels occur as pilots sometimes enter the various lock systems on the Great Lakes by using the side of the locks as a guide to align the vessel for passage. This heavy abrasion makes for a skinned up freeboard. A heavy buildup of “frog hair” marine growth from the deep load line to the bilge turn is also usually present. Fleet engineers want this removed as it can slow the vessel’s speed by 1-1.5 knots. With time equating to money, this is an important task to complete (Figure 1).

The underwater hull suffers a similar fate of heavy abrasion. Many Great Lakes ports have not been regularly dredged and the Lakers (slang for Great Lake’s freighters) end up dragging the bottom coming into or out of port fully loaded. The turn of the bilge area is particularly at risk for heavy abrasion.

For all this work to be done there is still a schedule to maintain and a budget to keep. Dry dock fees alone, exclusive of any repair fees, for the largest Lakers often run into the high six figures. With these large expenses, delays for inclement weather to complete a paint job are rarely tolerated as work continues 24 hours a day, seven days a week while the boat is in dry dock.

Equipment for Painting

Painting in low temperatures has created many modifications of equipment to cope with these conditions. One of the modifications is to outfit a container box as a paint kitchen. Changes include hard piping the box for an air supply, bolting two to three airless spray pumps on the wall and hard wiring explosion proof electrical connections and lights. The pumps are typically 45:1 to 70:1 in size. The larger pumps are preferred as spray hose lengths are 500 feet to 600 feet (152 m to 183 m) long. The hoses are not heated and sit on the cold concrete floor of a dry dock, which is often coated with ice. A hole is cut into the door and warm air is piped into box. The temperature inside the kitchen is maintained between 35°F (2°C) and 45°F (7°C).

This self-contained kitchen is lowered to the floor of the dry dock and is rarely moved. Yard personnel mix the paint and keep an extra supply of paint in this kitchen. It is also used as a warming house for the blast and paint crews working outside.

Personal protective equipment consists of the standard hardhat, full-face respirator, and fall protection equipment. Extra clothing, gloves, and an Andes Mountain style hat to protect the ears worn underneath the hard hat help keep the worker as warm as possible.

Another method used with success in these temperatures is to have a tarp draped from the handrails of the ship to the top rail of the dry dock, either floating or graving. This helps keep the abrasive used for surface preparation contained along with providing protection from the elements. In this configuration a heater is attached to the pump. The paint is heated between 90°F (32°C) and 110°F (43°C). With hundreds of feet of spray hose laying on the cold floor of a dry dock the paint loses temperature fast but is warm enough to get the paint onto the surface being coated.

Surface Preparation and Paint

Surface preparation is typically an abrasive blast per SSPC-SP7 Brush Blast. In some situations a more thorough blast is required to accommodate higher performance coatings or entirely remove failed or excessively thick coatings. (Learn more about abrasive blasting in Blast Pressure: How to Get It Right.)

There are also situations where lead paint on the vessel cannot be removed. Abrasive blasting is not possible, as the contamination cannot be cleaned up from the dry dock due to ice on the floor. Containment is not feasible due to budget and time constraints. Pressure washing is out of the question as the water in sub-freezing temperatures would make an ideal skating rink on the dry dock floor and make clean up impossible. In these situations small areas are cleaned per SSPC-SP3 Hand Tool Cleaning with an epoxy coating applied over a very marginally prepared surface.

Other situations where minimal surface preparation has been used include vessels not in a dry dock. These include vessels that are painted while frozen in the ice next to an occupied dry dock and vessels frozen in a river while docked at a pier. In the first example workers stand on the ice, walk completely around the vessel, use extension poles and paint the free board. In the other situation workers paint the free board that is pier side while standing on the ground. The water side/ice side painting is then done from a basket attached to a crane, hanging the basket over the deck and painting the opposite free board when the ice was not safe to traverse. (Further discussion of less than ideal surface preparation can be found in The Treatment of Rusted Surfaces When Proper Surface Preparation Is Not an Option.)

The type of protective coating used is dependent on the owner’s request, budget and area being painted. Phenalkamine epoxies are typically used on the underwater hull and as a first coat on the freeboard. Depending on the temperature, thinning with the recommended solvent is almost always done to reduce the viscosity of cold paint. Moisture curing zincs have also been used successfully in below zero Fahrenheit (less than -17°C) temperatures. Topcoats include acrylic polyurethanes, polyester urethanes, alkyd modified urethanes, acrylic modified alkyds, and moisture cure urethanes.

Cargo hold coatings have included flake filled amine epoxies with a low temperature hardener and plural component elastomers. Polyureas have been used on some work boat decks. Low temperature pre-mixed aggregate epoxies have been used on the automobile deck of car ferries.

Case Study

A 700-foot (213-meters) Great Lakes bulk carrier came into dry dock in January. Its main cargo had been road salt. The exterior freeboard was heavily corroded and the owner wanted a new paint job. To beef up the corrosion protection, a zinc primer was used versus the standard epoxy. The challenge was that the ambient temperature was -7°F (-22°C) and the surface temperature was -3°F (-19°C).

The decision was made to use a singlepack moisture cure urethane organic zinc with four ounces of a moisture scavenging amine accelerator per gallon. The intermediate coat would be a phenalkamine epoxy followed by a single component acrylic modified alkyd topcoat. This unusual topcoat for this system was chosen for its future ease of touch up and repairs by the crew of the vessel.

The starboard area to be painted was 25 feet high by 400 feet long. The surface was abrasive blasted per SSPC SP6 Commercial Blast. A 70:1 pump with 500 feet of hose and a 521 tip were used to apply the coating. There were two pot tenders mixing and feeding the pump along with a man lift driver and sprayer in the bucket.

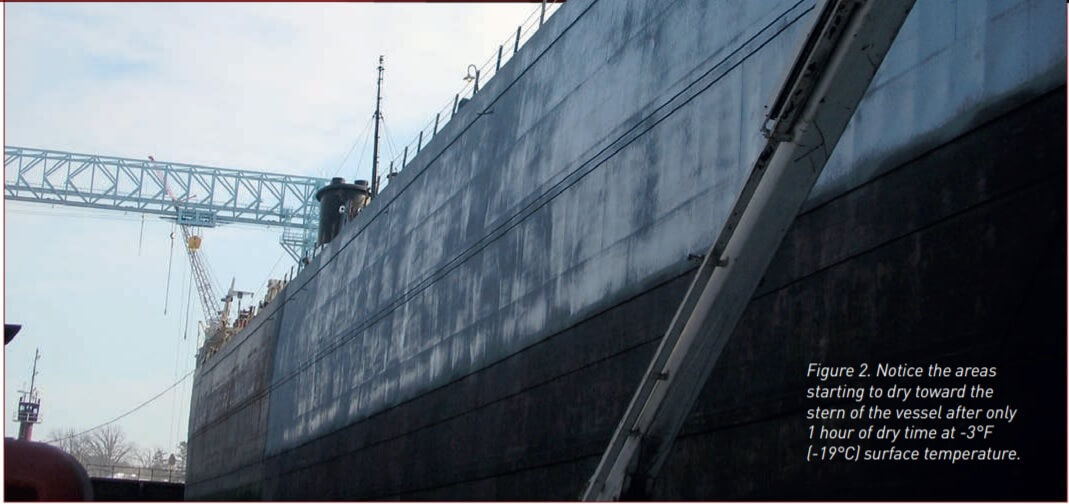

Painting application began at 11:45 am. The area was completed at 2:00 pm. By the time the first coat of zinc primer had been completed, the coating applied to the first 50 feet had begun to flash off and was mostly dry to the touch (Figure 2). At 3:00 pm a coin rub adhesion test was done to check the integrity and adhesion of the paint film. The results convinced the shipyard to proceed. They began applying the intermediate coat of epoxy at 3:00 pm and completed around 5:45 pm. The topcoat was applied the next day.

Another challenge faced by northern dry docks in the winter is ice buildup on the vessel’s hull. After a boat is layed up and sits dockside for its turn in the dry dock, ice builds up on the underwater hull and freeboard. This can make for some interesting uses of equipment to remove that ice. Some shipyards have a bubbler system in place for waiting boats. That system has marginal success, particularly if the temperature is really cold. The other piece of equipment used to remove ice in preparation for painting is the forklift. After the boat is docked and with ice hanging on the side of the vessel, the operator will take the forks and catch an edge of the ice on the hull. They then move the forks up and have it act as a lever on the edge and remove large chunks of ice. To quantify, the ice is THICK. Many times this build up can be over 12” thick, so this can be a dangerous situation as large pieces of ice are peeled from the hull.

Many times the ice falls off the aft end of the ship by itself. The heat generated inside by keeping the engine room warm for interior work and crew comfort radiates through the steel and breaks the bond of the ice from the hull. This sometimes creates a safety issue as large “glacial” size chunks of ice fall onto the floor of the dry dock. Proper safety procedures have to be followed at all times. (See Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5).

As you can see in Figure 5, sometimes the ice does not come off. In these situations crews work around the ice and those areas just don’t get painted.

Another interesting contradiction is that the shipyards prefer colder temperatures, that is, in the 10°F to 15°F (-12°C to -9°C) range for this winter work. When the temperature gets too warm the sun heats the deck, usually above freezing. This in turn begins to melt any ice and snow that may have accumulated on the deck. The resultant runoff flows over the deck edge and down the side of the freeboard. Two things happen. The water flows to the dry dock floor, refreezes, and creates an ice rink, and the water runs over the deck edge, freezes and creates an ice flow on the freeboard. With an ice flow on the freeboard, painting of those unpainted areas is interrupted and, if freshly painted, those surfaces are usually damaged and have to be repaired (Figure 6).

Conclusions

Painting outside in the cold winter weather is a frequent occurrence. Attention to the temperature of the coating either with a “warming house” storage unit or actual heating of the paint with heaters is paramount. Equipment requirements are not stringent but larger pumps are needed to adequately spray cold paint and service long lengths of hose. Budget and time constraints force the shipyard to push the envelope in regards to accepted painting practices and following a manufacturer’s recommendations. The trade-off is getting a job done on time with usually only a small amount of repair for violating those accepted practices.

Below freezing temperatures, bring it on! It’s a great day to paint.