Over recent years, there have been interesting developments in the way that coatings are specified, which have resulted in issues that can make it impossible to meet a marine paint specification as currently written.

First of all, the increase in demand for offshore structures and the move by many shipyards into the offshore market has seen owner paint inspectors moving into shipyards, often resulting in much tighter subjective and objective requirements being placed on the yard during the build process.

There has always been a problem in terms of meeting paint specification because of the subjective nature of some of the assessments—for example, visual assessment of surface cleanliness, rust and mill scale removal, dust and profile height when using a surface comparator. (For more about specifications, read Coatings Specifications, Good, Bad or Ugly: Lou Vincent Q&A.)

It is well known that the surface appearance can change considerably depending on the nature of the blast medium used, making an assessment of surface cleanliness subjective.

Secondly, up to 2008, the shipbuilding boom and the strong market for shipping has seen a considerable demand for ships, as well as attractive charter rates that encouraged owners to accept ships as quickly as possible.

Many of the Chinese yards and some of the second-tier South Korean yards were established in this boom time and therefore developed systems and processes in line with what owners were then willing to accept—vessels that were perhaps of a lesser standard than may have been accepted if there was not such a boom.

Oil rig under construction at Shipyard Chiwan. Photo: SteKrueBe, Creative Commons.

Now that market conditions have worsened considerably, owners are being more cautious about what is and is not acceptable, and standards have tightened. This has posed difficulties to yards that grew up in the boom time, including many of the larger new Chinese yards.

These yards developed their systems based on owners’ expectations during the boom period and are now struggling to meet the higher expectations. Owners in the meantime are being frustrated by what is now perceived as poor quality performance that, although acceptable in the boom time, is not so acceptable during the recession.

Clearly this is not the case for all yards and all owners, but there does seem to be inconsistencies that the industry should work to overcome.

Standards Changes

In addition to these changes, the advent of the IMO performance, Standard for Protective Coatings (IMO PSPC) has seen an increased focus on coating for all areas of the vessel, but specifically for ballast tanks. In particular, the PSPC introduced the concept of a minimum dry film thickness (DFT) based on the 90:10 rule.

This article will focus on the problems being faced in meeting specified DFT, which is considered the best understood and the most objective element of application. We will show that even this most basic aspect of the paint specification is neither well understood nor well specified. (Related reading: The Impact of Minimum & Maximum DFT Values on Coating Performance.)

Essential Dry Film Thickness (DFT)

If the coating process cannot achieve the specified DFT, then to some extent the coating system performance through-life may be compromised.

Any such reduction in performance could manifest itself in many ways (if at all), for example:

- Increased chance of corrosion for a low DFT

- Increased chance of cracking for a high DFT

- Increase in time to service

- Solvent entrapment

“As Applied” vs. “Specified Scheme”

First of all, let us consider a typical specification as required by the IMO PSPC for water ballast tanks for the majority of areas (rather than repairs and erection joints):

Surface preparation

Sa 2.5 (Note: This is a requirement for mill scale and rust removal; it does not cover the specification of profile height.)

Paint scheme

Multi-coat system to an nominal DFT of 320 µm with up to two stripe coats. (In most cases, this is interpreted as 2×160 µm and one stripe coat.)

Requirement

Minimum DFT: Defined by the 90:10 rule.

Maximum DFT: In accordance with manufacturer’s recommendations.

In general, there is also wording in the PSPC that indicates that the coating is to be applied in accordance with manufacturer’s recommendations. This may seem fairly straightforward, as may a specification for the underwater hull, such as:

The scheme specified:

- 2x epoxy anti-corrosive – 250 µm

- 1x modified epoxy – 100 µm

- 3 x self-polishing antifouling – 390 µm

- Total scheme DFT – 740 µm

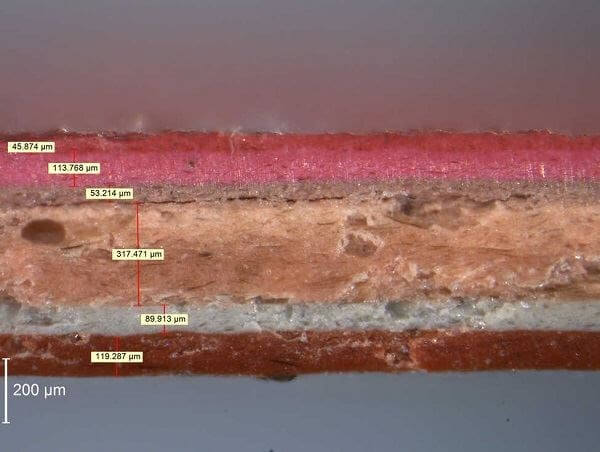

The fact that reality can vary considerably from the specification can be considered in the specifications above for this example of an underwater hull coating system specification:

The scheme as applied:

- 2x epoxy anti-corrosive – 209 µm

- 1x modified epoxy 317 – µm

- 3x self-polishing antifouling – 213 µm

- Total scheme DFT – 739 µm

Keeping in mind that many of the major commercial shipyards procedures now only afford owners’ representatives the opportunity to assess cleanliness and final DFT as a standard procedure, then there is considerable opportunity for the “as-applied” system to bear little or no relation to the “specified scheme”. If the scheme applied was assessed based on two inspections—surface cleanliness and final DFT—then the scheme would likely be accepted (if these were the only hold points). The scheme would be accepted despite the low epoxy anti-corrosive and self-polishing anti-fouling layer thicknesses.

This situation, combined with a total lack of “as-applied” records (even with the presence of a coating technical file as required by the PSPC), results in considerable problems when trying to determine causes of a failure.

This deviation from the scheme specified, in many instances, will of course result in a reduction to the performance of the total scheme in service. The degree of reduction in performance can vary considerably depending on the type of product and its performance requirements.

***

This article was co-written with John Fletcher.

With more than 45 years’ experience in the corrosion, protective coatings and electronic inspection technology fields, John Fletcher serves as technical support manager at Elcometer Ltd. in Manchester, England. He is the current president of the Institute of Corrosion (iCorr), and chairman of ASTM International Committee D01 on Paint and Related Coatings, Materials and Applications. As a top international expert in paint testing and inspection methods, Fletcher also leads Subcommittee D01.23 on Physical Properties of Applied Paint Film.